Genealogical research comes with unsettling insights about our ancestors. Case in point is documentation I have uncovered about my ancestor Francis Dorsett (my great-great-great-great-great grandfather) and his son John Dorsett (my direct descendent).

Genealogical research comes with unsettling insights about our ancestors. Case in point is documentation I have uncovered about my ancestor Francis Dorsett (my great-great-great-great-great grandfather) and his son John Dorsett (my direct descendent).

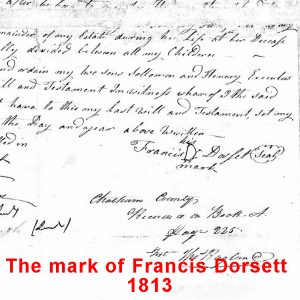

Francis was born in England in 1740 and migrated to the United States. The family settled in Chatham County, North Carolina. (West of Raleigh). Francis served in the Revolutionary War by furnishing supplies. Upon his death in 1813, he owned 277 acres of land. A complete inventory of possessions is fascinating and includes the following:

- a hymn book and Bible, although he was illiterate,

- one looking glass,

- one wagon,

- blacksmith tools,

- Livestock: seventeen hogs, three horses, two cattle, four sheep,

- Kitchenware: two kettles, two pots, one skillet, one tea kettle, one set of teaware (sic), and

- One Negro Woman, Mime. (Note: Mime was left to Francis’s wife, Rebecca, in his will.)

Rebecca was fortunate as he left her one-third of his property until her death. Then, the lands went to his sons. The custom was, at the time, to leave daughters nothing. However, he did leave Mime’s future firstborn child to his daughter as well as Mime, herself, upon Rebecca’s demise.

His son, John, was born in 1760 and married at the age of twenty. I have been unable to find any record of his marriage license, but that is not surprising. During that time, most ordinary people did not have a formal ceremony because of the cost of the license. The couple simply made the announcement to families or friends three times, and their marriage was acknowledged. Known as banns, this was the way the poor married in England at the time.

By the mid-1700s, the local government recognized this as a legal form of marriage. However, the banns had to be read by a government official or by a clergyman from the Church of England. Church of England ministers were the only ones who could perform the ceremony. Those of other religions often chose not to legally marry under these conditions.

John had four children with his first wife, Jemima Ann, including my great-great-great-grandfather, Hezekiah. After Jemima died in 1834, John remarried at the age of seventy-six. His bride was eighteen-year-old Polly Mobley. They went on to have five children before his death at the age of ninety-one.

Polly was lucky. John left her his property as well as his slave, Andus, so she could continue to raise his three sons. At her death, the remainder of the estate went to his male heirs with Polly. His two daughters received nothing.

Both slavery and treating women as second-class citizens is abhorrent to me. And a seventy-six-year-old man marrying a teenager? Don’t get me started. (I’ve taken to calling him the lecher.) And yet, my forbearers participated in these activities. They were, in effect, a product of their times and followed standard practices.

I cannot change the past, but I can change the future. We owe it to future generations to examine our traditions and culture and cull those patterns that denigrate others. By walking this talk, we will make the world a better place for those who come after us.

Sources:

Wood, Maren L., “Marriage in Colonial North America” accessed May 23, 2020 at https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/marriage-colonial-north.

Recent Comments